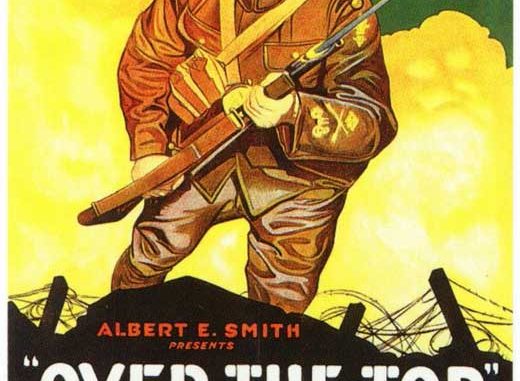

Over the Top by Arthur Guy Empey provides a first-hand account of World War I from the perspective of an American serving in a British unit. Written with a mixture of grim realism and patriotic fervour, the book serves as both a compelling personal narrative and a propaganda tool designed to encourage American support for the war. While its chronology is somewhat disjointed, and certain details regarding Empey’s unit affiliation remain ambiguous, the novel successfully captures the brutal conditions of trench warfare and the resilience of the men who endured them.

The book does not follow a strict chronological order, instead presenting a series of experiences from Empey’s time in the trenches. Common themes include the omnipresence of lice (“cooties”), the misery of the mud-filled trenches, the ever-present danger of artillery fire, and the emotional toll of war. Empey’s writing provides vivid, often gruesome descriptions of life on the front lines, punctuated by moments of humour, camaraderie, and hardship.

Despite the grim realities of war, Empey highlights the humour and resilience of British soldiers. He challenges the stereotype of the reserved Englishman, instead portraying “Tommy” as a cheerful and humorous mate: “To the average American who has not lived and fought with him, the Englishman appears to be distant, reserved, a slow thinker, and lacking in humor… but from my association with the man who inhabits the British Isles, I find that this opinion is unjust.” Even in the worst conditions, soldiers joke, sing, and maintain an air of light-heartedness. Songs such as “Pack up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag” feature prominently, and there are frequent jests at the expense of new recruits and officers alike.

Empey’s account is not merely a personal memoir but a deliberate piece of wartime propaganda aimed at encouraging American support for the conflict. His description of encountering a British recruitment poster featuring Lord Kitchener is particularly striking: “The one that impressed me most was a life-size picture of Lord Kitchener with his finger pointing directly at me, under the caption of ‘Your King and Country Need You.’ No matter which way I turned, the accusing finger followed me.” Empey’s narrative suggests that it was a moral duty—even for an American—to take up arms in defence of Britain. This theme is reinforced in his encounter with a young civilian whom he berates for not enlisting: “Aren’t you ashamed of yourself, a husky young chap like you in mufti when men are needed in the trenches? Here I am, an American… to fight for your King and Country.”

The book does not shy away from the harsh realities of war. The descriptions of conditions in the trenches are particularly harrowing, filled with accounts of mud, rats, lice, and relentless bombardment. The constant presence of death, whether through artillery fire, snipers, or disease, is depicted in unsettling detail. Empey writes: “We lived, ate, and slept in that trench with the unburied dead for six days. It was awful to watch their faces become swollen and discoloured. Towards the last the stench was fierce.” The novel also addresses the terror of artillery bombardment: “From the waist up I was all enthusiasm, but from there down, everything was missing. I thought I should die with fright.”

Unlike many other soldier’s memoirs, Over the Top does not engage in open criticism of the military hierarchy. Empey presents British officers as competent and fair, a portrayal that reinforces the book’s role as a morale-boosting tool. The harsh discipline of the British Army is acknowledged but never condemned: “There are about seven million ways of breaking the King’s Regulations; to keep one you have to break another.” A notable scene describes the harsh punishment for failing to pass messages along the trench, with the offending soldier sentenced to 21 days of “crucifixion” (being tied to a limber wheel). However, such discipline is presented as necessary rather than excessive.

Despite the horrors of war, Empey emphasises that activity and morale-building were essential for maintaining the fighting spirit. The organisation of makeshift theatres and games in rest billets provided much-needed respite: “I taught them how to pitch horseshoes, and this game made a great hit… Then Tommy turned to America for a new diversion.” The makeshift theatre productions, including The Diamond Palace Saloon and competition with the 56th Divisional concert party, The Bow Bells, showcase the importance of entertainment in preserving sanity amidst the chaos.