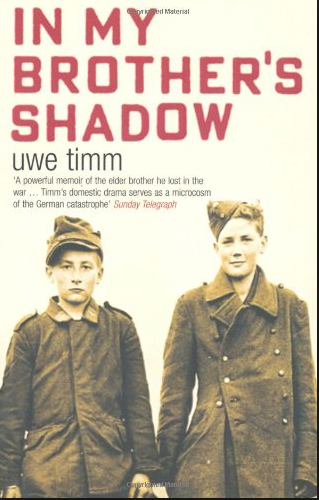

Uwe Timm’s book explores the life of his brother Franz-Heinz, a member of the Waffen SS and the impact Franz-Heinz’s death had on his parents and Uwe’s relationship with them in post-war West Germany.

Uwe Timm’s book explores the life of his brother Franz-Heinz, a member of the Waffen SS and the impact Franz-Heinz’s death had on his parents and Uwe’s relationship with them in post-war West Germany.

Born in 1940, Uwe was the youngest of three siblings in a middle-class Hamburg family. Franz-Heinz was Uwe’s senior by 16 years and he joined the SS Death’s Head Division, being killed in action in October 1943.[1] Uwe has only one memory of Franz-Heinz and the book explores how his brother’s death shaped his childhood. Franz-Heinz left a diary of his time at the front, along with letters to his parents and Uwe uses these to ‘reconstruct’ the brother he did not know and find out who he was and what he did in Russia.

Uwe recalls that Franz Heinz ‘accompanied me through my childhood, absent and yet present in my mother’s grief, my father’s doubts, the hints my parents dropped when they were talking to each other. They told stories about him, little tales of situations that were similar, showing how brave and decent he was. Even when he wasn’t the subject of discussion he was still present, more present than other dead people, in anecdotes and photographs, and in the comparisons, my father drew with me, the younger son, the afterthought.’[2]

He added that ‘my impression today, gleaned from my memory, it that my father suffered more from the loss of his son than my mother. She had said goodbye to him in her grieving, her indignation found a focus, that bunch of rogues…meaning the Nazis…[were blamed]…My father could not allow himself to grieve, only feel anger, but because he saw courage, duty and traditions as inviolable virtues he directed his anger not at the real causes but only at military bunglers, shirkers and traitors.’[3]

Uwe focuses on how many Germans dealt with the war and processed the crimes that were committed through by the German State and its organs. He comments the Waffen SS and Wehrmacht (German army) were believed by many Germans to have had ‘nothing to do with those terrible things [holocaust]. In the 1950s and early 1960s, the Wehrmacht had a reputation for decency. The Wehrmacht were only soldiers who had only been doing their duty’.[4]

He also finds these double standard hard to take. Franz-Heinz comments in one letter to his father on 11 August 1943 about the British air raids on Hamburg. He said ‘I’m worried about everyone at home, we hear reports of air raids by the English every day. If only they’d stop that filthy business. It’s not war, it’s the murder of women and children – it’s inhumane’.[5] Uwe comments that ‘it is hard to comprehend and impossible to trace the way in which sympathy and compassion in the face of suffering could be blanked out, while a distinction emerged between humanity at home and humanity in Russia. In Russia, the killing of civilians is normal, everyday work, not even worth mentioning at home its murder’.[6]

This is a fascinating book about how the war affected people and continues to resonate through families to this day. However, it does not contain a reproduction of Franz Heinz’s letters or diary which would have been a useful historical source to put in the public domain.

Notes:

[1] Uwe Timm, In My Brother’s Shadow (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), p.2.

[2] Ibid., p.2.

[3] Ibid., p.67.

[4] Ibid., p.54.

[5] Ibid., p.18.

[6] Ibid., p.82.